There are moments in time, however tragic they may be, that change the course of history and even force changes for the good.

May 1, 1994, was one of those seminal moments in the history of Formula One. Arguably the greatest driver to have graced the sport until then, Ayrton Senna da Silva suffered a fatal crash on the seventh lap of the San Marino Grand Prix while leading the race at the now-infamous Tamburello corner of the Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari circuit in Imola.

It marked one of the darkest chapters in the championship since its inception in 1950. Senna’s crash on Sunday was the second fatality of that weekend after Roland Ratzenberger had lost his life during qualifying on Saturday. The Austrian driver hit a wall at high speed when his Simtek Ford suffered a front-wing failure. In fact, it was F1’s weekend from hell. On Friday, another Brazilian, Rubens Barichello, had a severe crash during practice when he hit a kerb and got launched into the barriers. Only the timely intervention of F1 doctor Sid Watkins saved his life.

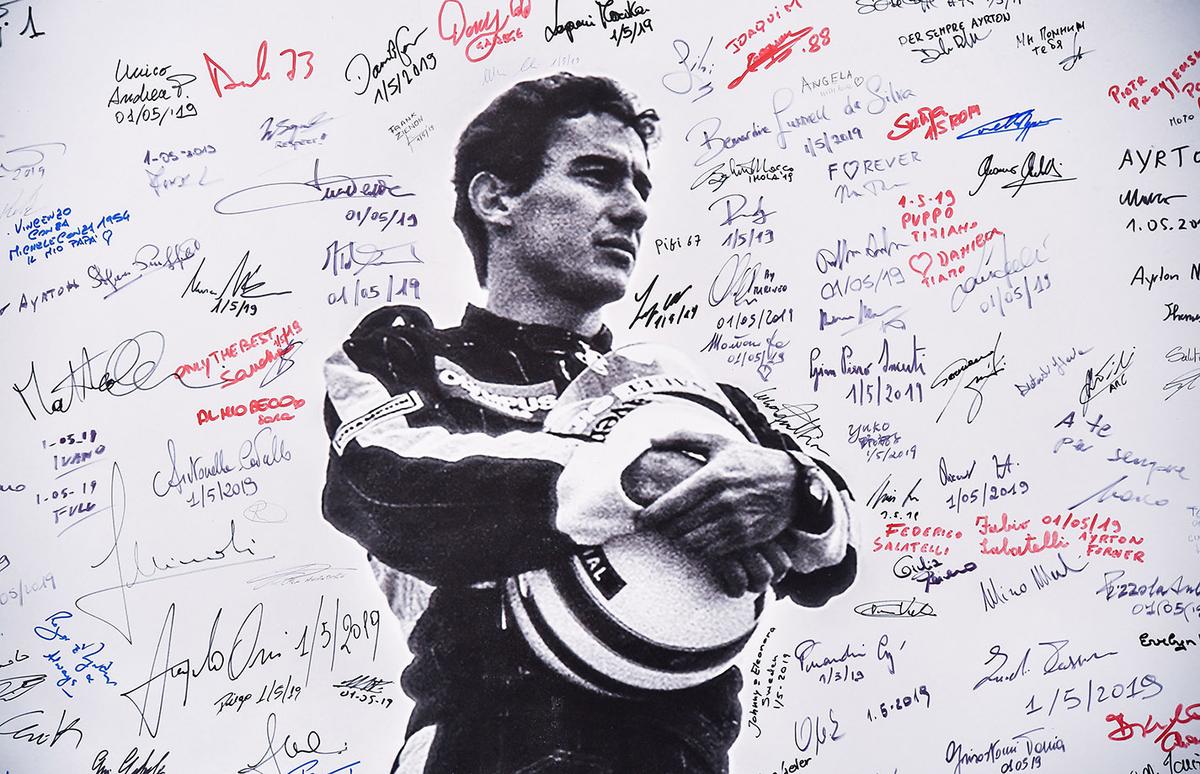

A poster bearing a photo of Brazilian F1 driver Ayrton Senna signed by fans is displayed during a ceremony on May 1, 2019 marking the 25th anniversary of the death of Brazilian’s F1 driver Ayrton Senna at the Imola “Enzo and Dino Ferrari” circuit during the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The three-time World champion moved to the all-conquering Williams F1 team for the ’94 season after his long stint with McLaren, where he had won all his titles. In 1992 and 1993, Williams dominated the sport after mastering the Active Suspension Technology, powering Nigel Mansell and Alain Prost to the driver’s crown. However, in 1994, the FIA banned electronic driver aids like active suspension, traction control and launch control. And Williams struggled during the initial part of the season.

Senna did not score points in the first two races when he crashed out in his home race in Brazil before being taken out by Mika Hakkinen in the second one in Aida, Japan. In Imola, the Brazilian took pole position. There was a massive crash on the opening lap. Pedro Lamy, in his Lotus, hit the rear of JJ Lheto’s Benetton, which stalled on the grid. The Safety Car was brought in to clear the debris for the next five laps before racing resumed on lap six.

THE GIST

Senna, known for his talent in rainy races, did not have a good result in his first kart race on a wet track. Because of that, he trained every day until he became a master in this condition

The Brazilian’s favourite track was Spa in Belgium, a circuit where he won five times in F1

Senna always dreamed of, but never raced for, Ferrari. But Luca di Montezemolo, then president of the Italian team, revealed that there were strong negotiations as early as 1994 to make this happen. “He wanted to come to Ferrari and I wanted him on the team,” said the manager

The striking helmet worn by Senna throughout his career was inspired by the design used by the Brazilian delegation at the 1979 Karting World Championship

On lap seven, Senna’s car veered straight into the concrete barrier as it approached the fast left-hander Tamburello corner. The driver suffered severe injuries when one of the tyres hit his helmet while a piece of suspension also pierced past his visor. There have been many theories surrounding the reason for the crash, from a driver mistake or a puncture to a steering column failure and even a drop in tyre pressure due to running behind a very slow Safety Car. Senna was given emergency treatment at the track before being airlifted to a hospital in Bologna, where he was pronounced dead three hours later.

Prior to the events in Imola, F1 had not seen a casualty during a race meeting since Riccardo Paletti’s fatal crash at the 1982 Canadian Grand Prix. The deaths of Ratzenberger and Senna sent shockwaves across the world and illustrated the dangerous nature of motorsport.

It was the kind of rude awakening the sport needed. Leading up to Imola 1994, there were apprehensions that cars were getting faster and safety needed to be improved. The fact that one of the best, if not THE best, the sport has seen succumbed woke the powers that be out of their slumber.

The memorial statue of Formula One World Champion Ayrton Senna in Imola, Italy on 8 July 2017.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Immediately, the FIA sprung into action, and a slew of safety measures have been enforced since then, making F1 one of the safest categories of motorsport.

Some changes to the car included raised cockpit sides to protect the head, better headrest protection, and wheel tethers.

One of the most significant advances was the introduction of the Head and Neck Support (HANS) device in the early 2000s. The HANS device is attached to the driver’s helmet and, as the name suggests, significantly reduces the impact on the head and neck. Many drivers have avoided severe impacts since then. Though drivers initially resisted it as it restricted their movement, it has become ubiquitous across most categories.

More recently, the Halo device – a wishbone-like structure around the cockpit was introduced in 2018 to protect a loose wheel or, at times, even the wheels of another airborne car from hitting the driver’s helmet. The wheel tethers ensure the tyres don’t come loose quickly in case of a big crash or suspension damage.

Apart from the changes to the car, much work has been done on circuit safety in terms of barriers, run-offs, and fences. F1 has constantly reviewed safety measures and updated tyre and TechPro barriers to find ways to reduce the impact on the driver during violent crashes. Modern circuits have many asphalt run-off areas, which helps drivers avoid crashes even if they run wide.

However, the flip side of these has been that there is a perception that drivers don’t pay the penalty for going off, which has taken the challenge out of the sport. It is a tricky balance between safety and fairness, but begrudgingly, safety has been prioritised.

The fact that Formula One did not see another driver fatality for another 21 years showed the sport’s remarkable progress since that fateful weekend in Imola in 1994. In 2015, Jules Bianchi became the first driver since Senna to die because of an accident at an F1 race. During the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix, the Marussia driver hit a recovery vehicle attending to another stricken car away from the race track. But in damp conditions, Bianchi ran wide and hit the recovery vehicle, and his car slid under the wheel-loader, causing a significant head injury. In a way, the accident further accelerated the need for a device like a halo to protect the cockpit without losing the essence of what F1 is – an open-wheel, open-cockpit racing series.

A lot of credit also has to go to the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association (GPDA), which has worked closely with circuit promoters, the FIA and F1 to advance safety measures. Incidentally, on the morning of May 1, Senna proposed reviving the GPDA – which was disbanded between 1982 and 1994 – after Ratzenberger’s death and offered to lead the organisation. The modern version of GPDA came into being immediately after the events of Imola. While Senna’s blinding speed, mastery of wet conditions, and ability to be hard-nosed in battle are what people will remember him for, the Brazilian left an indelible mark even from the beyond, ensuring the sport he lorded over is safer even if it required his ultimate sacrifice.